Redesigning the Food Pyramid

A Review of Proposed Improvements to the USDA Food Guide

by Jim English

In In 1992 the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) introduced the first official Food Guide. The food guide—presented in the graphic form of a “pyramid”—was an early attempt to educate the public with a simplified list of dietary recommendations thought to improve health and reduce incidence of chronic diseases. The current ubiquity of the food pyramid is a good measure of just how successful the guide has been in bamboozling the American public. In the short span of twenty years, the pyramid revolutionized the dietary habits of tens of millions of people and is the basis on which many doctors, nutritionists, laypersons and food producers alike judge the quality of the diet.

Although the pyramid appeared sound at the time it was produced, and continues to carry the ring of authority, many of its recommendations are now recognized to be flawed, based on emerging research. For the last decade, the food guide has been criticized by scientists for being outmoded and presenting recommendations that are potentially harmful.

Carbo Loading and Obesity

One of the most far-reaching concepts promoted by the pyramid was the notion that obesity and heart disease are linked to the consumption of fats. This concept gave rise to a nutritional orthodoxy that dictated that the majority of calories should come from complex carbohydrates—primarily breads, cereals, rice, pasta, potatoes and other starches (up to 11 servings a day!).

Additionally, meats, fish, eggs, and other protein sources were relegated to relatively small portions (2 to 3 servings per day), while fats were severely restricted (the guide grouped fats and oils with sweets and recommended “use sparingly”). Many researchers have pointed out that the practice of switching dietary fats for carbohydrates—particularly those found in

the food pyramid—mirrors the start of the rise in obesity that is currently at epidemic proportions.

|

Building a Better Pyramid

In response to growing criticism, the USDA’s Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion is currently re-evaluating the food pyramid. At this same time, a group of Harvard researchers has already proposed a revised food pyramid. In the January, 2003 issue of Scientific American, Walter C. Willett and Meir J. Stampfer, professors of epidemiology and nutrition at the

Harvard School of Public Health, introduced a food guide incorporating improvements designed to address many of the problems in the old pyramid. In their article, “Rebuilding the Food Pyramid,” Willett and Stampfer proposed new nutritional recommendations that are based, in large part, on a recent study they co-authored in the December 2002 issue of the Journal of

Clinical Nutrition (see abstract).

Reducing Intake of Carbs

Willet and Stampfer point out that the USDA pyramid provides misleading guidance by “promoting the consumption of complex carbohydrates and eschewing fats and oils,” stating, “not all fats are bad for you, and by no means are all complex carbohydrates good for you.” Complex carbohydrates form the base of the current USDA food pyramid, yet scientists have found little

evidence to show that high daily intake of carbohydrates provides any benefit. Refined carbohydrates, such as white bread and white rice, are quickly broken down in the body, causing rapid elevation of blood glucose levels. This jump in blood sugar levels triggers a large release of insulin. Insulin subsequently clears glucose from the blood, leading to increased feelings of

hunger. In short, eating carbohydrates contributes to overeating and obesity. Even eating a potato, which is mainly starch, raises blood sugar levels higher than eating the same amount of calories from table sugar. “In our epidemiological studies, we have found that a high intake of starch from refined grains and potatoes is associated with a high risk of type 2 diabetes

and coronary heart disease. Conversely, a greater intake of fiber is related to a lower risk of these illnesses.”

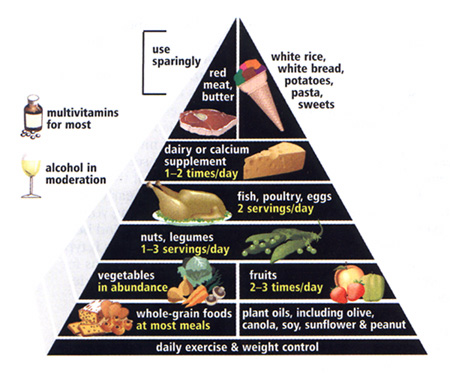

To address this imbalance Willett and Stampfer redesigned their food pyramid by first moving white rice, white bread, potatoes, pasta and refined carbohydrates from the foundation (base) of the pyramid up to the top with a “use sparingly” recommendation. And they still recommend eating carbohydrates at most meals, but the list of approved carbs are derived from “healthy carbohydrates,” in the form of whole grain foods, such as whole wheat bread, oatmeal and brown rice.

New Respect for Dietary Fats

As mentioned previously, the USDA pyramid radically altered the role of dietary fats in the American diet. This is because the original intent of nutritionists who designed the food guide was to convey a simple message—saturated fats (found in red meat and dairy products) raise cholesterol levels and increase risks of developing cardiovascular disease. Willett and Stampfer

observe that, “The notion that fat in general is to be avoided stems mainly from observations that affluent Western countries have both high intakes of fat and high rates of coronary heart disease. They point out that this correlation, however, is limited to saturated fat. Societies in which people eat relatively large portions of monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fat

tend to have lower rates of heart disease.” Unfortunately the “all fat is bad” message so effectively conveyed by the USDA pyramid obscured numerous studies showing that polyunsaturated fats, as found in fish —can actually reduce cholesterol levels.

To correct the unbalanced view of fats codified in the old pyramid, Willett and Stampfer drew on previous research gleaned from the 1976 Nurses’ Health Study, and the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study in 1986. When researchers compared fat intake of some 90,000 women and 50,000 men, they found the risk of heart disease increased substantially when eating trans-fats, and only slightly when eating saturated fats. By contrast, a diet that contained both monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats was actually found to decrease the risk of cardiovascular disease. Researchers observed that, since these two effects counterbalanced each other, “higher overall consumption of fat did not lead to higher rates of coronary heart disease.” Noting that these findings “reinforced a 1989 report by the National Academy of Sciences that concluded that total fat intake alone was not associated with heart disease risk.”

Willett and Stampfer also challenge the idea, promoted by the American Heart Association and other groups, that people get no more than 30 percent of daily calories from fat. “This 30 percent limit has become so entrenched among nutritionists that even the sophisticated observer could be forgiven for thinking that many studies must show that individuals with that level of fat intake enjoyed better health than those with higher levels. But no study has demonstrated long-term health benefits that can be directly attributed to a low-fat diet. The 30 percent limit on fat was essentially drawn from thin air.”

Willett and Stampfer now recommend a healthy diet that includes generous servings of unsaturated fats, including liquid vegetable oils—especially olive and fish oils. “If both the fats and carbohydrates in your diet are healthy, you probably do not have to worry too much about the percentages of total calories coming from each.” Trans fat does not appear at all in the pyramid, because “it has no place in a healthy diet.”

Eat Plenty of Vegetables, Fruit

Willett and Stampfer note that high intake of fruits and vegetables is perhaps “the least controversial aspect of the food pyramid,” and recommend both should be eaten in abundance. Interestingly they note that while reductions in risk of cancer are widely promoted, evidence for this comes from case-control studies that are susceptible to numerous biases, pointing out

that recent findings from large prospective studies tend to show “little relation between overall fruit and vegetable consumption and cancer incidence. (Specific nutrients in fruits and vegetables may offer benefits, though; for instance, the folic acid in green leafy vegetables may reduce the risk of colon cancer, and the lycopene found in tomatoes may lower the risk of

[lung and] prostate cancer.)”

Where Willett and Stampfer see a significant value in fruits and vegetables is in their ability to reduce cardiovascular disease. “Fruits and vegetables are also the primary source of many vitamins needed for good health. Thus, there are good reasons to consume the recommended five servings a day, even if doing so has little impact on cancer risk.”

New Guidelines on Protein Sources

The revised pyramid addresses another flaw in the USDA pyramid by recognizing important health differences between red meats (beef, pork and lamb) and the other foods in the meat and beans group (poultry, fish, legumes, nuts and eggs). Red meats, which are high in saturated fat and cholesterol, are associated with an increased risk of coronary heart disease, Type 2 diabetes

and colon cancer. By contrast, poultry and fish contain less saturated fats, and fish are a good source of essential Omega-3 fatty acids. “Not surprisingly, studies have shown that people who replace red meat with chicken and fish have a lower risk of coronary heart disease and colon cancer.”

Willett and Stampfer also recommend up to three servings per day of nuts. Nuts, which were restricted in the old guide, likely due to their high fat content, are actually a good source of unsaturated fats. Research has shown that “nuts improve blood cholesterol ratios, and epidemiological studies indicate that they lower the risk of heart disease and diabetes.” They also note that people who eat nuts are “actually less likely to be obese; perhaps because nuts are more satisfying to the appetite, eating them seems to have the effect of significantly reducing the intake of other foods.”

Cut Back on Dairy Products

Another issue addressed by the new food guide is the old recommendation of consuming the equivalent of two or three glasses of milk a day. This advice was based on the belief that dairy products provide calcium, which was thought to help prevent osteoporosis and bone fractures. “But the highest rates of fractures are found in countries with high dairy consumption, and

large prospective studies have not shown a lower risk of fractures among those who eat plenty of dairy products. Calcium is an essential nutrient, but the requirements for bone health have probably been overstated.”

Willett and Stampfer also challenge the notion that high dairy consumption is safe: “in several studies, men who consumed large amounts of dairy products experienced an increased risk of prostate cancer, and in some studies, women with high intakes had elevated rates of ovarian cancer. Although fat was initially assumed to be the responsible factor, this has not been supported in more detailed analysis. High calcium intake itself seemed most clearly related to the risk of prostate cancer. More research is needed to determine the health effects of dairy products, but at the moment it seems imprudent to recommend high consumption.”

Daily Exercise, a Multivitamin and Moderate Alcohol Use

Last, but not least, Willet and Stampfer have replaced the bottom of the USDA pyramid (previously recommending up to 11 servings of complex carbohydrates) with a program of daily exercise to aid in weight control. They also recommend a daily multivitamin for most people, and allow alcohol consumption as an option (if not contraindicated by specific health conditions or

medications) based on numerous studies showing moderate alcohol consumption to be of benefit to the cardiovascular system.

Proof of Concept

To demonstrate that their improved pyramid is actually healthier than the current USDA model, Willett and Stampfer, along with their colleagues in the Harvard study, created the Alternative Healthy Eating Index (AHEI) to measure what happens when people follow their dietary recommendations. When epidemiological studies were compared to the new index the researchers

discovered that men and women following the new guidelines have a lower risk of chronic diseases, particularly cardiovascular disease. They state, “This benefit resulted almost entirely from significant reductions in the risk of cardiovascular disease—up to 30 percent for women and 40 percent for men.”

Conclusion

While the USDA continues to review the old food guide, Willett and Stampfer have presented a new pyramid—based on twenty years of research —that incorporates dietary strategies that are proven to improve health. Willett and Stampfer recommend eating vegetables and fruits in abundance, along with moderate amounts of healthy sources of protein (nuts, legumes, fish, poultry

and eggs). They also recommend cutting back on consumption of refined grains (including white bread, white rice and white pasta), potatoes and sugar, and cutting consumption of dairy products to one or two servings a day. Studies indicate that adherence to the recommendations in the revised pyramid can significantly reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease for both men and

women, and reduce incidence of diabetes.

These recommendations are also more in line with the dietary recommendations of Drs. Robert Atkins, Barry Sears, and Vladimir Dilman.

References

1. Willett, W.C., Stampfer, M.J. Rebuilding the Food Pyramid, Scientific American, Jan. 2003., Vol. 288, No. 1:64-69.

2. McCullough, M.L., Feskanich, D., Stampfer, M.J., Giovannucci, E.L., Rimm, E.B., Hu, F.B., Spiegelman, D., Hunter, D.J., Colditz, G.A., Willett, W.C. Diet Quality and Major Chronic Disease Risk in Men and Women: Moving Toward Improved Dietary Guidance. Am J Clin Nutr 2002;76:126171.

|

Abstract McCullough ML, Feskanich D, Stampfer MJ, Giovannucci EL, Rimm EB, Hu FB, Spiegelman D, Hunter DJ, Colditz GA, Willett WC. BACKGROUND: Adherence to the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, measured with the US Department of Agriculture Healthy Eating Index (HEI), was associated with only a small reduction in major chronic disease risk. Research suggests that greater reductions in risk are possible with more specific guidance. OBJECTIVE: We evaluated whether 2 alternate measures of diet quality, the Alternate Healthy Eating Index (AHEI) and the Recommended Food Score (RFS), would predict chronic disease risk reduction more effectively than did the HEI. DESIGN: A total of 38 615 men from the Health Professional’s Follow-up Study and 67 271 women from the Nurses’ Health Study completed dietary questionnaires. Major chronic disease was defined as the initial occurrence of cardiovascular disease (CVD), cancer, or nontraumatic death during 8-12 y of follow-up. RESULTS: High AHEI scores were associated with significant reductions in risk of major chronic disease in men [multivariate relative risk (RR): 0.80; 95% CI: 0.71, 0.91] and in women (RR: 0.89; 95% CI: 0.82, 0.96) when comparing the highest and lowest quintiles. Reductions in risk were particularly strong for CVD in men (RR: 0.61; 95% CI: 0.49, 0.75) and in women (RR: 0.72; 95% CI: 0.60, 0.86). In men but not in women, the RFS predicted risk of major chronic disease (RR: 0.93; 95% CI: 0.83, 1.04) and CVD (RR: 0.77; 95% CI: 0.64, 0.93). CONCLUSIONS: The AHEI predicted chronic disease risk better than did the RFS (or the HEI, in our previous research) primarily because of a strong inverse association with CVD. Dietary guidelines can be improved by providing more specific and comprehensive advice. |